Internet Stack Protocol:

1 Transport-Layer services

The transport Layer manages the logical communication between application processes running on different hosts, whereas the network layer manages the logical communication between host.

The fact that there are multiple processes running on the same host calls for the need for multiplexing and demultiplexing.

The Sender in transport protocols breaks application messages into segments and passes them to the network layer (to the IP).

The Receiver in transport protocols reassembles these segments into messages and demultiplexes them to the application layer via a socket.

2 Multiplexing and Demultiplexing

2.1 Multiplexing

Multiplexing is done at the sender: data from multiple sockets is handled, to which the respective transport header is added, later used for demultiplexing.

2.2 Demultiplexing

The transport header info is used to deliver the received segment to the correct socket.

Multiplexing and demultiplexing are done based on segment and datagram header field values.

2.2.1 Connectionless demultiplexing

- the host receives IP datagrams.

- each datagram has a source IP address and a destination IP address

- each datagram carries one transport-layer segment

- each segment has source and destination port numbers

- the host uses the IP address and the port number to direct the segment to the appropriate socket.

2.2.2 Connection-Oriented demultiplexing

The TCP socket gets identified by 4 tuples:

- source IP address

- source port number

- destination IP address

- destination port number

The receiver uses all four of this values (4-tuple, quadrupla di informazioni) to direct the segment to the appropriate socket.

A server may support many simultaneous TCP sockets:

- each socket is identified by its own 4-tuple

- each socket is associated with a different connecting client

In TCP a connection is identified by 4 parameters!

3 Connectionless transport: UDP

RFC 768:

UDP (User datagram protocol) is a “best effort” service, like IP.

Segments may be lost and delivered out of order to the application.

This because UDP is connectionless: there is no handshake between UDP sender and receiver, each UDP segment is handled independently of others.

3.1 Benefits and Uses

- no connection

- connection can add RTT delay

- simplicity

- small header size

- no flow and congestion control

- UDP can go faster

- still works under congestion

This leads to UDP being useful in these areas:

- streaming and multimedia applications (loss tolerant, rate sensitive)

- DNS

- SNMP

- HTTP/3

If a reliable transfer is needed over UDP (for example in HTTP/3) reliability and congestion control are added at the application layer.

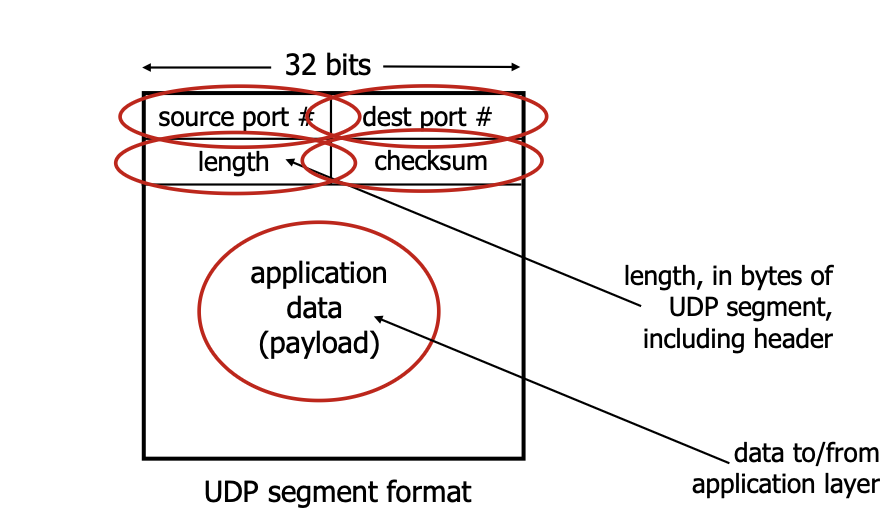

3.2 UDP segment header

UDP segment header:

- the payload is a message from the application layer, it is of variable length so we have the length field

- length field: length of the UDP segment (including header) in bytes

3.3 UDP checksum

The sender treats the contents of the UDP segment (header and IP address included) as a sequence of 16-bit integers, then the checksum is computed as the sum of these 16-bit integers and the checksum value is put into the UDP checksum field.

The receiver computes the checksum aswell and compares it to the checksum included in the header: if these are not equal and error is detected.

4 Connection-Oriented transport: TCP (3.5)

RFCs: 793,1122, 2018, 5681, 7323

TCP (transport control protocol) introduces the point-to-point concept: one sender, one receiver.

It achieves a reliable, in-order byte stream, from the application standpoint.

The flow is Full duplex: the flow is bidirectional in the same connection.

Every segment has an MSS: maximum segment size: dimensione frame - dimensione massima dell’ether IP (20 byte) - dimensione massima dell’ether TCP (20 byte)

The TCP congestion and flow control set the window size of the pipelining (3.2 Pipelining).

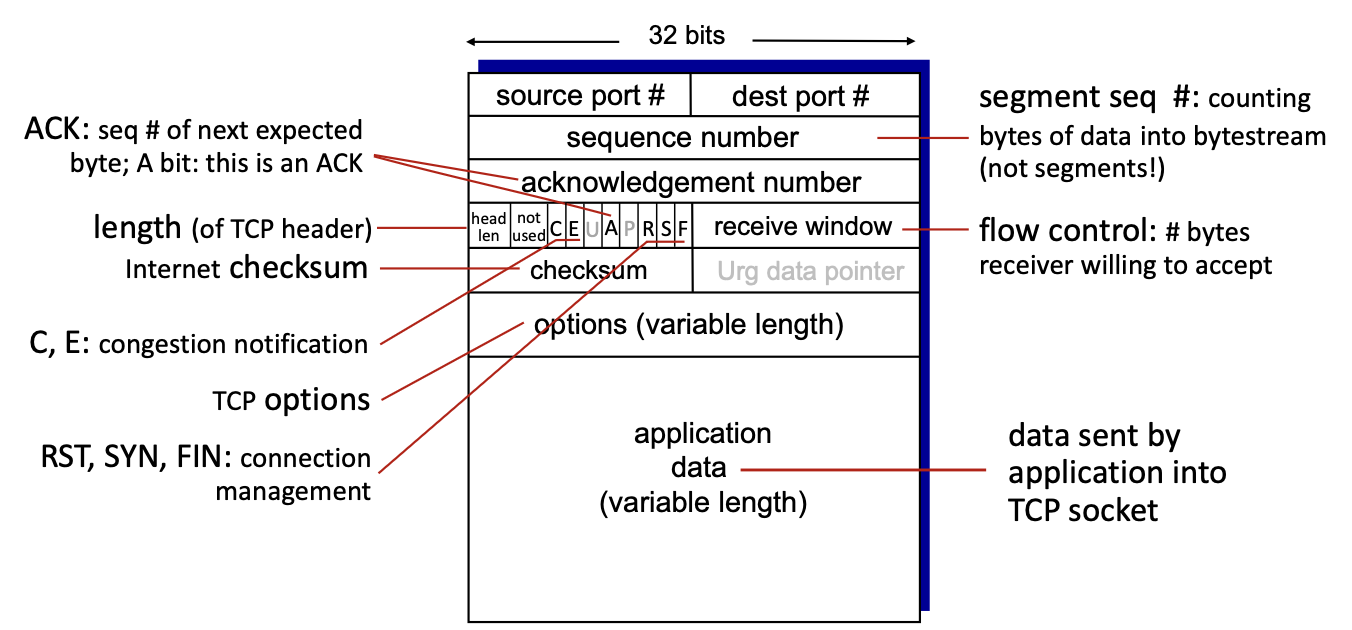

4.1 TCP segment structure (3.5.2)

TCP segment structure:

- PDLated approach: ACKs are sent inside fragments

- if A bit is set “Acknowledgement number” is significant (significativo)

- the checksum is the same as in UDP: internet checksum

- R: RST: reset: when connection is having problems and the connection needs a reset

- S: SYN: start: is set in the connection phase

- F: FIN: finish: is set when wanting to close the connection

- receive window: used to repeatedly tell the other end how many bytes are free in the receiving window

- “urgent data pointer”: used to tell receiver that in the payload is important data (with priority). Is never used. When this field is significant, bit “U” in the flags is set.

normally the header is 5 words (5* 32 bits = 20 byte), but it is of variable length, the length is inside the “header length” field

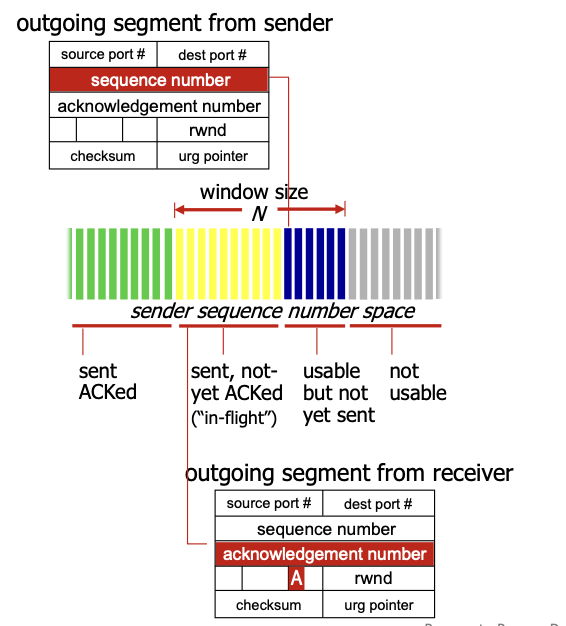

4.2 Sequence Numbers and ACKs

In TCP sequence numbers are the byte stream number of the first byte in the segment’s data.

TCP Window:

TCP uses a go-back- error recovering approach: it sends cumulative ACKs (see 3.2.1.1 Go-back-N).

TCP doesn’t specify how the receiver must handle out-of-order segments, that is up to the implementor.

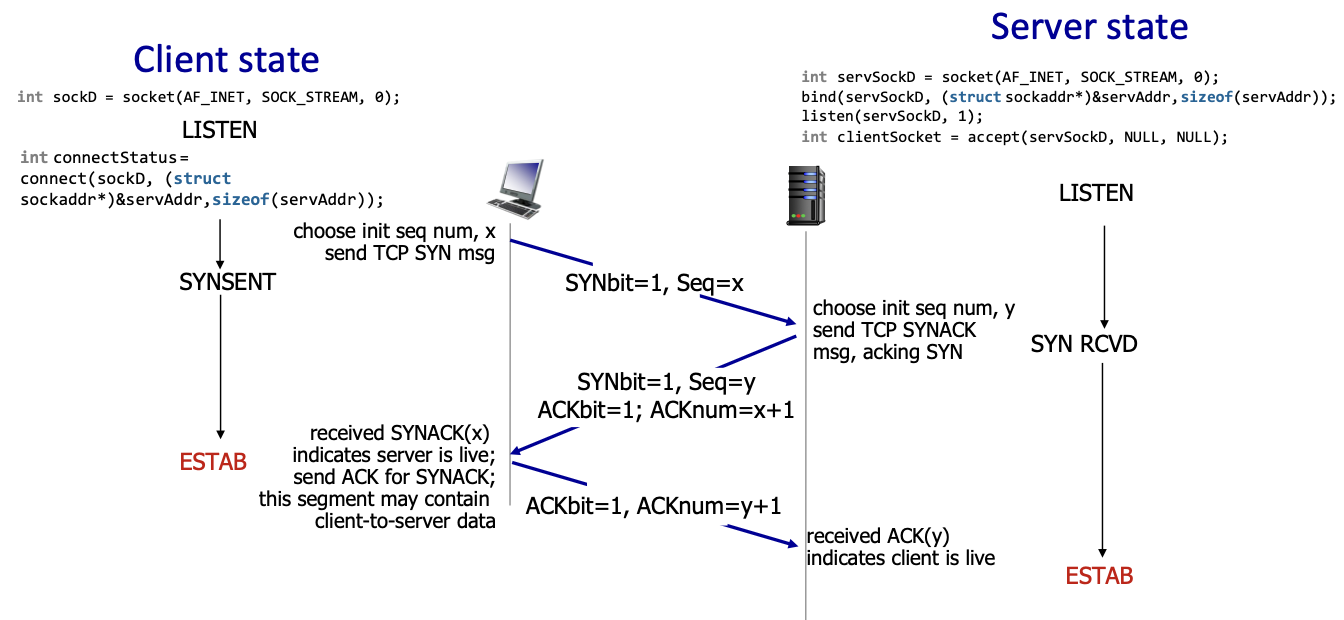

4.3 TCP connection Management

Before exchanging data, the sender and the receiver handshake: they agree to establish a connection and agree on the connection parameters (for example the starting sequence numbers).

4.3.1 the 3-way handshake

tcp 3-way handshake:

- if the initial sequence number was always the same, we risk mixing segments from two different connections, so we use a random number.

EG: we have a first connection which is short, every packet is ACKd and the connection is closed, then we open a new connection shortly after, if there are still segments from connection 1 “in flight” the risk is they arrive while we have initiated the second connection, these segments arrive and are mistaken for segments from the new connection.

4.3.2 Closing a TCP connection

- client sends TCP FIN control segment

- server receives the FIN and replies with an ACK, closes the connection and sends a FIN

- client receives the FIN, replies with an ACK and starts a timed wait (designed to close the connection shortly after the supposed arrival of the ACK to the server)

- server receives the ACK. The connection is now closed.

If the server doesn’t receive the ACK (it timeouts), it resends the FIN, this is the reason of the timed wait of the client.

What does it mean to “close a connection”?

Deallocating the data needed for the connection.

4.4 TCP reliable data transfer (3.5.4)

The TCP protocol creates a RDT service (3 Reliable Data transfer (RDT) protocol) on top of IP’s (3 IP the internet protocol) unreliable service.

This is a window-based ARQ scheme: ?

- acknowledgements

- timeouts

- retransmissions

4.4.1 TCP Timeout (3.5.3)

How do we set a TCP timeout value?

It needs to be longer than RTT, if it is too short we get a premature timeout which leads no unnecessary retransmissions, if it is too long we have a slow reaction to segment loss.

But we first need to estimante RTT: we send a sampleRTT: we measure the time from the segment transmission until the ACK receipt.

Obviously we use the average of the most recents sampleRTTs, not just the last one.

We compute the exponential weighted moving average (EWMA):

- where is the LAST measured sampleRTT

- the influence of past samples decreases exponentially fast

- a typical value for is (). The bigger the more responsive is the estimate (but less stable).

When computing the first ERTT () we consider

esercizio: scrivere la stima da n=0 a n=4 (sampleRTT:=RTT , estimatedRTT:=ERTT) :

What happens if a packet gets retransmitted? How do we correctly measure the RTT? The best option is to ignore retransmitted packets when estimating RTT.

The timeout interval is estimatedRTT + “safety margin”.

If we are in a network with a large variation in the estimatedRTT we’ll use a larger safety margin.

where DevRTT is the safety margin: it is the EWMA of sampleRTT deviation from estimatedRTT:

where typically ().

4.4.2 TCP sender

- event: data received from application

- create segment with sequence number

- sequence number is the byte stream number of first data byte in the segment

- start timer if it isn’t already running

- sort of a timer for the older unACKed segment

- expiration interval:

TimeOutInterval

- event: timeout

- retransmit the segment that caused the timeout

- restart the timer

- event: ACK received

- if ACK acknowledges previously unACKed segments:

- update what is known to be ACKed

- start timer if there are still unACKed segments

- if ACK acknowledges previously unACKed segments:

pseudocode

NextSeqNum = InitialSeqNum

SendBase = InitialSeqNum

loop (forever) {

switch(event)

event: data received from application above

create TCP segment with sequence number NextSeqNum

if (timer currently not running)

{start timer}

pass segment to IP

NextSeqNum = NextSeqNum + length(data)

event: timer timeout

retransmit not-yet-acknowledged segment with smallest sequence number

start timer

event: ACK received, with ACK field value of y

if (y > SendBase) {

SendBase = y

if (there are currently not-yet-acknowledged segments)

{start timer}

}

} /* end of loop forever */4.4.3 TCP receiver

ACK generation (RFC 5681)

| EVENT AT RECEIVER | TCP RECEIVER ACTION |

|---|---|

| arrival of in-order segment with expected seq# . All data up to expected seq# is already ACKed | delayed ACK. Wait up to 500ms for the next segment. If no next segment, send ACK |

| arrival of in-order segment with the expected seq# . One other segment has pending ACK | immediately send a single cumulative ACK, ACKing both the in-order segments |

| arrival of out-of-order segment, higher than the expected seq# . A Gap is detected | immediately send a duplicate ACK, indicating the seq# of the next expected byte |

| arrival of segment that partially or completely fills the Gap | immediately send ACK, provided that the segment starts at the lower end of the gap |

4.4.4 TCP fast retransmit

If the sender receives 3 additional ACKs for the same data (“triple duplicate ACKs”), resend the unACKed segment with the smallest seq#, because it likely got lost, this way we don’t have to wait for the timeout.

4.5 TCP flow control (3.5.5)

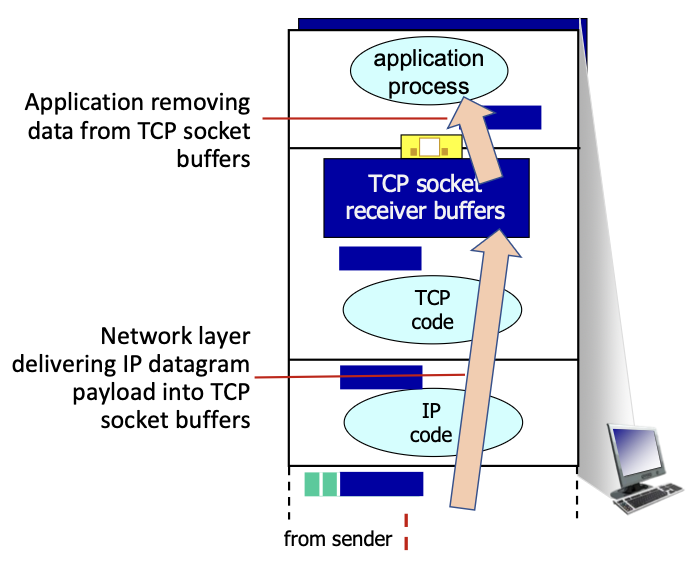

When the network layer delivers data faster than the speed at which the application layer removes data from the socket buffers we lose segments:

TCP receiver protocol stack:

We need to introduce flow control: the receiver controls the sender, so that no overflow occurs.

The TCP receiver advertises the free buffer space in the rwnd (“receive window”) field in the TCP header (4.1 TCP segment structure).

The sender limits the amount of unACKed (“in flight”) data to the received rwnd, this way we guarantee that the buffer will not overflow.

The receiver sets RcvBuffer via socket options (the default is typically 4096 bytes), many systems auto-adjust RcvBuffer.

receiver buffer:

The receiver windows is computed as follows:

So the transmitter sends this many bytes:

4.6 TCP congestion control (3.6)

Congestion is informally defined as follows: too many sources are sending too much data too fast for the network to handle.

At the router’s input ports are arriving more datagrams for time unit than how many datagrams for time unit the router can send.

This may happen either because the receiver has a too small input capacity, or because of internal congestion.

Congestion brings:

- long delays (because of queueing in router’s buffers)

- packet loss (buffer overflow at routers)

4.6.1 The causes of Congestion (3.6.1)

4.6.2 Approaches to congestion control (3.6.2)

One solution may be network-assisted congestion control: routers provide direct feedback to every sending and receiving host with flows passing through congested routers.

This feedback may indicate the congestion level or explicitly set a sending rate.

This approach is implemented by: ATM, DECbit and TCP ECN protocols.

End-to-end congestion control

The preferred approach is end-to-end congestion control: the network core does not provide direct feedback, congestion is inferred from observed loss and delay, this is the approach taken by TCP.

Remember packet loss not only is inferred from timeouts, but also from three duplicate ACKs (4.4.4 TCP fast retransmit).

The goal is to throttle the transmission rate just enough to avoid congestion.

Sender rate adjustment

We want the TCP sender to transmit as fast as possible, without congesting the network.

cwnd:

The sender limits its rate by limiting the number if unACKed bytes in the pipeline:

The sender is limited by: :

cwnd is dynamically adjusted in response to the perceived network congestion.

AIMD: Additive increase, multiplicative decrease

Senders can increase the sending rate, UNTIL packet loss (which means congestion) occurs, at which point the sending rate is decreased.

Each TCP sender sets its own rate based in implicit feedback (perceived congestion):

- ACK: segment received: network is not congested increase sending rate

- lost segment: either perceived by timeout or 3 duplicate ACKs: assume loss due to congestion: decrease sending rate

Additive increase: the sending rate is increased by 1 maximum segment size every RTT, until loss is detected.

Multiplicative Decrease: the sending rate is cut in half when loss is detected by triple duplicate ACK (TCP Reno), otherwise the sending rate is cut to 1 MSS (max seg size) when loss is detected by timeout (TCP Tahoe).

AIMD has been found to have desirable stability properties, is distributed and asynchronous.

4.6.3 TCP congestion control details

Congestion control is made of three phases:

- slow start

- congestion avoidance

- reaction to loss events

Slow Start

When a connection begins, the sending rate is increase exponentially until the first loss event:

we start with , cwnd is the doubled every RTT, which is done by incrementing cwnd for every ACK received. ?

When cwnd gets to the threshold value of ssthresh, the exponential increase gets switched to linear.

ssthresh is variable, initially set to 64KB, but is then adjusted (depending on cwnd, not on ssthresh) on loss events.

Congestion avoidance

Reaction to loss

When three duplicate ACKs are detected:

ssthresh = cwnd / 2cwnd = cwnd / 2 + 3 MSS- switch to fast recovery:

cwndincreases linearly starting fromcwnd / 2 + 3 MSS

When a timeout is detected:

ssthres = cwnd / 2cwnd = 1- switch to slow start:

cwndincreases exponentially starting from1

4.6.4 TCP cubic

There is a better way to “probe” for usable bandwidth:

We define as the sending rate at which the congestion loss was detected, we suppose the congestion state of the bottleneck link probably hasn’t changed much.

After a loss we cut as we said the windows in half, then we initially ramp to W_\max faster and we slow down the more we approach it.

This leads to the integral of the rate of transmission over time in TCP cubic is larger than the same integral in classic TCP, this means in average more segments are transmitted in the same time.

transmission rate over time:

TCP cubic is the default in linux and is the most popular TCP for popular Web Servers.

4.6.5 ECN: explicit congestion notification

TCP deployments often implement network-assisted congestion control:

- the ECN bits in the IP header’s ToS field get marked by the network router to indicate congestion. The policy for determining congestion is chosen by the network operator.

- This congestion indication is carried to the destination.

- The receiver sets the ECE (explicit congestion echo) bit on the ACK segment (bit E in the TCP segment), not notify the sender of the congestion.

- The sender on receipt of a set ECE bit, halves

cwndand setsCWR(control window reduced) in the next TCP segment header (bit C in the TCP segment).

This system involves both the IP protocol (ECN bit) and the TCP protocol (C and E bits).

4.6.6 TCP fairness

Since rate increase is linear and rate decrease is multiplicative, the rate at which senders transmit segments through a same node gets slowly evened out to , this means that TCP, under idealized assumptions, is fair (these assumptions are: same RTT for every sender, and fixed number of sessions only in congestion avoidance).

Transport services and fairness

Since UDP does not provide flow and congestion control, apps using it can send data at a constant, desired rate, this is not fair.

TCP applications in response can open multiple parallel connections between two hosts. Because of this lots of network administrators limit the amount of parallel connections between two hosts.

5 Evolution of transport-layer functionality

TCP and UDP have been the principale transport protocols for over 40 years.

In this time the functionality of these protocols has been expanded with application layer protocols.

5.1 Quic: quick UDP internet connections

This is an application-layer protocol on top of UDP.

It increases performance of HTTP by avoiding the TCP three way handshake and is deployed on many Google servers and apps.

QUIC employs:

- error and congestion control

- connection establishment: reliability, authentication, encryption

- multiple application-level “streams” multiplexed over a single QUIC connection

TLS vs QUIC: